Introduction

Knowing the policy process and terminology can help individuals feel more confident in meetings with legislative offices. This training introduces viewers to the language of policymaking, including steps in the legislative process, important vocabulary words, the main types of policies that exist, and how researchers can get involved.

Training Video

Purpose and Overview

This practice brief describes U.S. federal legislative processes with the aim to prepare social scientists for policy engagement. In particular, this brief may help guide targeted advocacy efforts by providing an overview of congressional committee jurisdiction for common social sciences topic areas. Also explained are legislative, budget, and appropriation processes with tips related to how a bill progresses. This brief may be useful for researchers or organizations engaging in legislative action at the national level.

Introduction to the Legislative Process

The process through which a bill becomes law is often slow and occurs in several stages (see Figure 1 below and corresponding numbers). Once a bill has been introduced by a member of Congress it is (1) referred by the House or Senate leadership to an appropriate committee or multiple committees in the chamber in which it was introduced. The bill may then be (2) referred to subcommittees for (3) hearings, (4) markups, and votes.

Markups are revisions and amendments proposed by committee members. A hearing involves testimony from witnesses or experts on the topic.

The committee may also kill the bill by pigeonholing.

Pigeonholing refers to a committee decision to kill a bill by refusing to assign it to a subcommittee, hold a hearing, or bring it to a vote. In sum, a committee can kill a bill by doing nothing at all.

If a committee (5) decides to move a bill through the process, they (6) write a report explaining the purpose and potential impact of the legislation and it is (7) sent to the full House or Senate floor for a debate and then a vote. In the House, the Speaker and the Majority Leader have control over which bills make it to the floor and can keep a bill from reaching a vote at all. In the Senate, a bill can be passed by unanimous consent, or hotlining.

Hotlining a bill bypasses the normal rules of order (e.g., debate) and goes straight to a vote. If one Senator votes ‘No’, unanimous consent is rejected. The dissent may be addressed, or the bill goes through the normal process.

Once either the House or the Senate has voted on a bill, they must (8 – see blue arrows) send it to the other chamber to be marked up, amended, and voted on. This process often produces two different versions of the bill that need to be reconciled 3 into a single piece of legislation. To do this, the bill is sent to a (9) conference committee made up of members of both the House and the Senate to reconcile differences and create one combined version of the bill.

Once the conference report has been passed by both chambers of Congress (see green arrows), the president has 10 days to make the decision (10) to either sign the bill into law or veto it or, if the president takes no action while Congress is in session, the bill automatically becomes law. If no action is taken by the president and Congress goes into recess, this is referred to as a pocket veto, and the bill does not become law. When the House and Senate go on recess, no votes are made; often, members go back to their districts and staff remain in the capitol working on policy issues between votes (House and Senate calendars are available online)

Referral to Committees

The committee is a critical step in the legislative process because many amendments to bills occur in committee, and because most bills do not make it past this step (i.e., most bills die in committee). It’s important to note that a committee is different from a caucus, as described below.

Committee

Caucus

A committee is formally established to consider legislation and conduct hearings within the jurisdiction prescribed to them. Members are assigned to committees as part of an official congressional responsibility. The lists of committees in the House and the Senate are available on their respective websites.

A caucus is an informal organization of legislators with similar policy concerns who gather to discuss issues, perform legislative research, and make policy plans. Being a member of a caucus is a voluntary affiliation. Unlike the House Caucuses and organizations, the Senate Caucuses are not formally registered.

When a piece of legislation is referred to Congress, the committee which has jurisdiction over it is not always clear resulting in some bills being assigned to multiple committees.

To avoid political issues over which committee has jurisdiction, it might be best to separate an expansive piece of legislation into multiple smaller bills with a clear committee jurisdiction. This can decrease the chance that the bill will get stuck in committee due to disputes over jurisdiction and increase the chances that the bill will make it to the floor for a vote.

The majority of bills that are written are amendments to existing law rather than starting from scratch. Attaching an amendment onto reauthorizations is also common because of the heightened likelihood the bill will progress through the legislative process.

Most bills die in the committee of the chamber where they are introduced.

Committee Jurisdiction

The following table has been organized into three main themes adapted for the social sciences and over-simplifies jurisdiction descriptions for this purpose. Committee jurisdiction over a bill may not always be clear, particularly in the case of expansive legislation, and some bills may be referred to multiple committees.

Federal Funding

Legislation can be used to effect change through the changes in regulation or federal funding. Many of the strategies and programs investigated by social sciences have implications for programmatic grant funding; therefore, the federal funding process is described further here. Authorization bills passed by Congress give the federal government legal authority to spend money on programs, and appropriations bills specify how much money will be allocated to each program. A program that has been authorized through enacted legislation is not funded unless money is allocated in the appropriations process. There are two types of spending: discretionary and mandatory.

Discretionary Spending

Mandatory Spending

Annual appropriations, e.g. grant programs

“Entitlements,” e.g. social security, Medicare/Medicaid

All spending must be authorized by Congress. Once it has been authorized, mandatory spending is not part of the appropriations process because money is automatically appropriated for entitlements. Authorizations can span multiple years so programs (like entitlements) do not need to be re-authorized each year.

The Appropriations Process

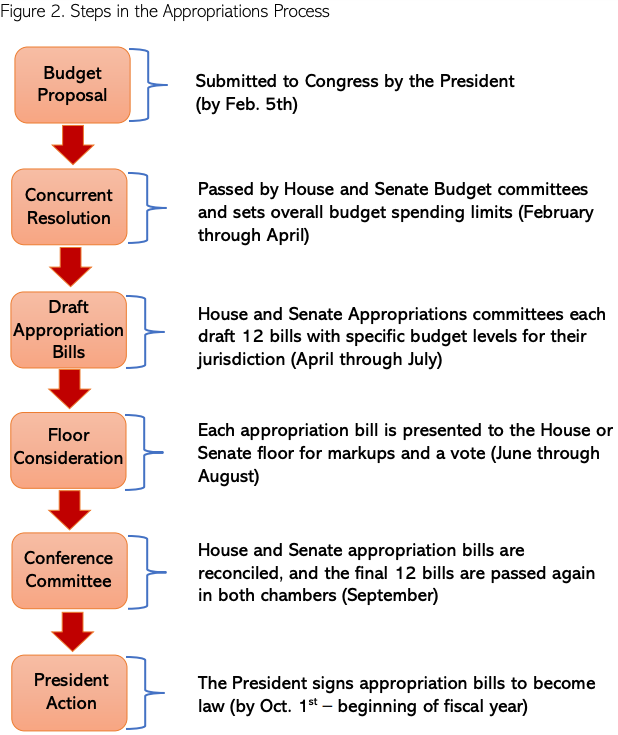

The budget is passed through Congress each year like any other piece of legislation. The budget process begins with the office of the President, then moves to congressional Budget Committees for a resolution that sets spending limits. Then the Appropriation Subcommittees (12 each in the House and Senate) draft appropriations bills with specific funding levels for their jurisdiction that must be enacted like all other legislation.

If Congress can’t agree on 12 separate appropriations bills, they can write a single bill encompassing multiple funding areas called an Omnibus bill.

If the budget process is not complete by Oct. 1, Congress can pass a continuing resolution to temporarily fund federal agencies.

The figure below depicts each step in the budget and appropriation process along with an approximate timeline for a fiscal year (Figure 2). The actual timeline varies and may be pushed back due to political disagreements and difficulty reconciling a final budget.

More Resources

| House | Senate | |

|---|---|---|

| Identify by Committee Assignment |

|

|

| Identify by State | Representatives by state | Senators by state |

| Caucuses and Other Member Organizations | Identify Caucuses and organizations registered in the House and their members | Senate Caucuses are not formal entities; therefore, Congress does not maintain a centralized list |

| Floor Proceedings and Schedule | House Floor Proceedings and Schedule | Senate Floor Proceedings and Schedule |

| Calendar (when is recess?) | House Calendar | Senate Calendar |